Ramanamaharishi25

Posted Date : 06:00 (22/03/2011)

·

ஸ்ரீரமண மகரிஷி

Ramanamaharishi:

Death Experience

If men get the urge to attain an object or realize a dream, a blind

haste envelops them and they are ill-prepared for the task on hand. They

bring about a frenetic milieu when they eat, sleep, find a seat in the

train, obtain Darśan in the temple, buy rice in the store… expressing a sense of nervousness.

store… expressing a sense of nervousness.

Not having a comprehensive sense of what they do, they perform deeds

with profit motive but without due thought. They don’t appreciate profit

rolls from diligent hard work.

Profit motive being the primary motive and consideration in their mind,

their effort is inadequate for the task on hand. Not knowing what they

do, they fly (work) in a sleep state.

They go in a hurried manner with Darśan of the Devata in the temple.

Their plan goes awry with them in a frenetic pace: Six-o’ clock rise from bed; 7 a.m. Darśan in the 1st

temple; with a time-limit of 30 minutes, 2nd temple visit;

8:30 a.m. at the 3rd temple; catch a bus for 4th Darśan at

10:30 a.m.; and the Saṅkarāchāriar

Mutt at 12 noon.

Here at the Mutt, I (the man in haste) get Darśan of Swamy and go for a

meal. I catch a siesta in the Mandapam. Then I go to the 5th

temple. They chase the clock at demoniacal speed going from temple to

temple.

The mind is not one-pointed in any temple.

What special event happened in the 2nd temple is not

known. Seeing the deity

with exhilaration and keeping the deity in the heart, mind and soul are

alien to them. ‘What that deity says and what the principles are:’ These

are not in the consciousness of the hyperactive personality even to size

of a germ in the rice paddy. Following the advice of someone to go to

the temples for their good, they make no enquiry and blindly follow the

advice. They brag to others

celebrating their whirlwind tour of umpteen temples, ‘I visited 12

temples in one day. That was one super-round.’ They don’t ask themselves

the benefits accrued by these visits. Thy don’t get to enjoy any

benefits from these umpteen temple visits.

The whirlwind temple visitors, show haste when they come visiting with Jñāṉis.

When the Jñāṉi

asks them, ‘What prompted you to visit with the beggarly me,’ they, on

tenterhooks, recite a mile-long list of wants: money, property, home,

jewels for wife, education for the children, ownership of cattle, land…

After Jñāni listened to the exhaustive list of wants, and said, ‘My

father offers his blessings to you,’ immediately with a sense of

satisfaction at the prospect of getting everything they asked for, they

whip the upper garment in a show of supreme accomplishment, put it back

on the shoulder and leave the premises.

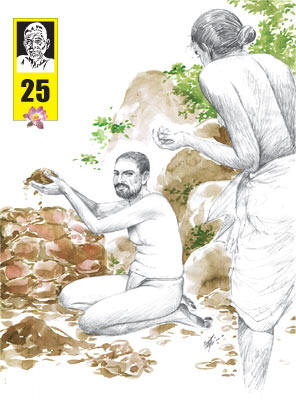

Bālaswāmy was building a raised platform all by himself outside the

Virūpākṣi

cave. He arranged small stones in piles, spread red earth on the pile

making it firm, and continued the process to build the platform. A man

rushed towards him from behind and asked him, ‘Where is the Swamy!’

Bālaswāmy was the only person there. Bālaswāmy said, ‘Swamy has just

left.’ The visitor in haste

asked, ‘When will he return.’ Bālaswāmy said, ‘I don’t know.’ Thinking

Swamy’s arrival will be late, he left the premises fast. When he was

going down the mountain, he saw Ecchammāl on her way up and told her,

‘Swamy is not up there.’ Ecchammāl knew for sure Swamy was up there. She

told him, ’Follow me, let us try again. I will show you the Swamy.’ The

visitor followed her.

She pointed out to Swamy polishing the surface of the newly built

platform and said to the visitor, ‘This the Swamy.’ The visitor was

surprised. He thought this is the Swamy who claimed no knowledge of the

whereabouts of the Swamy, and paid homage to him. He addressed Ecchammāl

and said, ‘He told me he did not know where Swamy was. Believing him, I

went down the mountain.’ He was put off.

We also face the same dilemma.

Why did compassionate Ramanamaharishi turn away an elderly man?

This was a lesson for the visitor.

This lesson teaches us, it was wrong for the visitor on hearing a

negative response from the builder of the platform, to go down in a

great haste. Compassionate Periyava wanted to offer Darśan to him.

Periyava spoke through Ecchammāl, brought him back up the

mountain so the visitor can

pay homage to him, offered blessings with his eyes of mercy and

continued with his construction work.

No true Jñāni admits he is a Jñāni. For the hastener (hasty person)

without the patience and tranquility, there is no need for a Jñāni.

At the same time, Jñāni allows for the haste, brings tranquility

to them with love and strength and draws him back to him. This is what

happened here. Who knows what was in Jñāni’s mind?

Close to Aṇṇāmalaiyār temple, there was a huge

Tamarind grove. A

Muslim leased it. The monkeys ate the tender tamarind pods.

They opened the mature pods and threw the wasted pods away. They

caused a great loss. He chased the monkeys away by using slingers and

stones. The monkeys screeched and scooted out of the grove. When he was

unawares, they returned and ate the tender pods and caused damage to the

mature pods. The Muslim

gentleman never wanted to kill the monkeys. His object was to chase them

away.

Once when he swung the slinger fast and discharged the stone, a money

sustained head injury from the flying stone and died. The Muslim was

afraid. The compatriots (the fellow monkeys) brought the dead monkey to Bālaswāmy, screeched

and cried. Bālaswāmy looked

at them with compassion. He offered solace to the monkeys, saying, ‘The

born die; the dead are reborn. This is the cycle of life and death. The

killer will die one day. Why do you grieve over it?’ The monkeys left

the place with the dead monkey.

The Islāmiyar

had fever that night. No treatment brought a relief or cure. Someone

told the Islāmiyar about simian’s complaint to Periyava; he was more

afraid. His relatives came

running to Bālaswāmy. They begged him to offer Vibhūti

to them. He told, that giving Vibhūti was not his practice, they

persisted and cried. Bālaswāmy took some ash from the nearby hearth and

gave it to the Muslim visitors.

That night itself, the Islāmiyar’s

illness left him.

If you approach a Jñāni in a proper manner and supplicate to him, he

will offer solace without doubt.

Many troubles vanish in his presence.

Love is the greatest Mantra of Jñāni. Rashness is the antithesis of

love. Rashness thinks of one’s self and never of anyone else. Thinking

of others as himself, the inside moves with rise of love.

One day in 1911 Bālaswāmy with two devotees (Vāsudevar

and Pazhaṉisāmi) took an oil-bath in Pacchaiamman temple pond and

returned up the mountain along the

Āmai

Pāṛai

path (Turtle Rock Path). Suddenly, Bālaswāmy felt dizzy, could not walk

and was short of breath. He sat on the rock. Later, he revealed what

happened to him. He explained the near-death experience in his own

words.

He narrated his near-death experience, “Suddenly my vision became

blurred. A white screen hid my vision. The tree, the plant, the vines

began gradually disappearing. Again, a white screen came and everything

disappeared. I sat to take rest. The white screen disappeared. The

objects appeared in my vision. The tree, the plant…appeared in my

vision. But the body lacked strength. Again, the white screen enveloped

me.

I reclined on the Turtle Rock and rested. Again, the sight came back.

For the third time, the white screen appeared. For the third time, the

white screen vanished. I felt the heartbeat losing its strength

resulting in slowing and obstruction of blood flow and ending in cardiac

arrest. My body turned blue.

Then, the fellow traveler Vasu, younger in age, not knowing what

death is, embraced me and cried. I heard Pazhaṉisāmi, older in years,

speak.

I felt the presence of devotees. I knew and felt the cardiac arrest.

But, I was not afraid. I sat cross-legged on the rock. I witnessed death

very carefully with no agitation.

For 15 minutes, I remained in Padmāsaṉa

pose. A

Śakti

made a dash from my body’s right side to the left side.

Because of it, my heart beat again. The blood flow was

regularized. The body slowly regained its natural complexion.

I was soaking wet in my perspiration. Slowly, I regained physical

strength and got up saying, ‘Let us go.’ It is not a state induced by

me. I had no desire to witness such an event.

I have no explanation for the event.

I had recurrent episodes like this. This time it was a little

longer.

When Bālaswāmy got up and walked, Vāsudevar jumped for joy.

All others sported blossoming faces. They shed tears of joy.

Bālaswāmy said to his devotees, ‘Why this crying. Did you think I was

dead? If I was to die, would I have not told you beforehand?’

This is like cardiac arrest.

All his descriptions are related to heart disease. This happens

with cardiac arrest. Profuse perspiration was an important sign of

cardiac arrest. That he remained calm and composed during his near-death

experience is noteworthy. Not worried about the pull of the body (to

eternity), he pulled himself away from near-death, and remained

self-realized in one place; this near-death experience is the witness.

Through this experience, it shows that, not afraid of death, he

remained in the loftiest place comfortably.

Many, afraid of dying, die. The self-realized person alone facing death

invites death without fear. He could even postpone his death.

Let us get Darśan.

Part 2

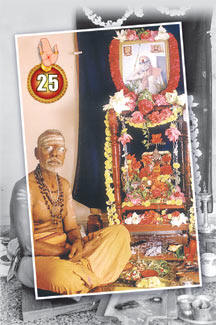

Deity of Mercy: Kanchi Mahan

Guru Darsan

Kāmātchidāsan Srinivasan is a gṛihastha (householder). He has no regular

income. But there was no lapse in the daily Puja service in the last 50

years, because of want of funds.

At

home, daily three pujas take place.

At

home, daily three pujas take place.

His home was resplendent with the grace of Srī

Kāmātchiammaṉ. His mind was always immersed in the thoughts of Periyava.

Kāmātchidāsan Srinivāsan

with a rising passion narrated an event to us.

Once nine Sannyasis came to Uththamathāṉapuram.

They all usually carried staffs in their hands.

Holding the staff is one religious duty (observance). It was

winter then. All nine

Sannyasis came to pay homage to Ambal.

They said to me, “Mahāperiyava sent us, saying, ‘I performed Puja for a

boy. If you have any doubts, ask him. He will clear them for you.’”

I was shocked. I was enveloped in fear hearing Periyava sent these

Sannyasis to a boy like me. I gathered courage and confidence and asked

them, “What doubts do you have?

சாதுர்மாசியம் cātur-māciyam.

Vow observed by Sannyāsins, which consists in their remaining in the

same place for two months in winter.

They narrated their doubts to me. But, I don’t remember what they asked

and what I told them in replies. I answered the questions like a boy who

committed the answers to memory and rattled them off to the Sannyasis.

Later, the Sannyāsīs narrated to Periyava all that I said to them. They

paid Namaskār

to him, saying, ‘We are eminently pleased.’

Not knowing any of these, I went to Periyava for Darśan.

He asked me, “I sent nine Sannyasis to see you. Did they visit

with you?”

I was trembling. I wondered whether I made any faux pas. I stammered,

“Yes Periyava… They came. I replied to their questions, Periyava.”

Periyava said, “They came and told me what all you said to them. You

said everything right. You have the favor and blessings of Kāmātchi.

That being so, how could you ever say anything wrong? He smiled and

raised his hand to offer his blessings.

That is when I was horripilated. With his eyes lighted up in

surprise, he narrated another incident.

That day, I was in Kanchipuram. A news out of the blue…’Periyava’s

order, Come immediately.’ I ran to see Periyava.

That day, I composed a poem that described flower decoration of

Periyava. With that poem

and his invitation in mind, I stood before him.

உடலைச் சிறிதுகூட அசைக்காமல்,

இறைசிந்தனையோடு லயித்திருப்பது

'காஷ்ட மௌனம்

=

Kāṣta

Mauṉam

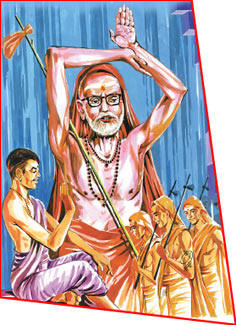

I heard Periyava’s voice, ‘Call him inside.’ I went inside. What I saw

on Periyava was the floral decoration of exquisite nature; it gave me a

kaleidoscopic feeling of surprise, confusion, wonder, happiness, fear…

From his seat to the crown, every part was decorated with flowers.

I fell flat on the floor and offered Namaskār.

Tears rolled down in streams. He asked me, ‘You have put the decoration

on me earlier in poetic words. Are you thinking of me all the time in

your mind?’

‘To me the servitor, Kāmātchi and Periyava are one:’ Saying those words

to Periyava, I offered my Namaskār again. The tears flowed freely from

my eyes.

‘Ok, read what you wrote!’ said Periyava. with joy, I read the poem. Its

meaning is…

‘Mahan’s lotus feet shine like the feet of Ambāḷ;

Mahan’s whole body shines with flower decoration; Mahan’s head is

decorated beautifully with flower crown; Mahan’s Yoga Staff is

concentrically decorated with flowers; Mahan’s chest shines with

universal visual delight of garland with Kadamba, Tulsi, Bael leaves…;

Mahan’s lotus feet shining like Spiritual eminence are placed on the

flowery sandals: that Mahan’s lotus feet, I carry on my head always and

attain supreme joy.

As I finished reading the poem, Periyava picked from the flower pile and

sprinkled the flower petals on his own head.

Periyava and the staff were decorated as described by me in the poem.

This decoration was the solemn promise and vow made originally by a

woman.

It is the grace and mercy of Kāmātchi that made it possible that a

servitor like me wrote the poem beforehand, and Periyava gave us the

holy appearance in the floral decoration to prove and illustrate my

poetic adoration of Periyava.

It is favor and privilege of divine nature that Periyava gave a

Darśan to me in floral decoration. What else could it be?

Kāmātchidāsan Srinivasan said it with supreme joy in a moving

way.

Darśan will continue.