Epistles from Eternity

Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

I was born in a village hugging close to a major

north-south corridor on the East Coast in south India.

For a small village of a few hundred people in the 1930s, it had

two temples dedicated to Draupadi, the polyandrous princess married to

Pandavas. The other one is the shrine of Siva and his family: Parvati,

Shanmuga and Ganesa.

There was a pond not far from our backyard but

close to the highway, the

cooling station for the local buffalos, and daring kids riding on and

taunting the buffalos while swimming in the brown water. The ubiquitous

thorn-bearing tree grew in abundance on its banks. As a child without

the footwear, I invariably stepped on the thorns. Because of the thorns,

the birds don’t build their nests. The migrating birds fly into the

thorns and lacerate their flesh. It thrives well even in a dry season.

It is a tree no one liked. We used to break its branches, chewed one end

and used it as a toothbrush.

My mother told me my grandfather used to go to a

nearby village on horseback to visit with his flame from the past.

Nothing more, I knew of him.

Years later as a medical student, I surmised he

probably died of atrial fibrillation, heart attack, cerebral hemorrhage

or some such catastrophic event.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I received an epistle from the midwife from her

eternal abode.

Once you had sores (impetigo) on your hands and feet during your childhood.

I applied herbal medicine. I burnt the dry leaves, suspended the ashes in

oil and applied it on your sores. They cleared. The deep sores (Ecthyma)

left scars on your legs.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Grandson:

You were only two years old when I died. You were

the love of my life, the apple of my eyes. As my soul floated away from

the body, I saw you seated on your mother's waist. I used to play with

you all the time. Yes, I had a few bad habits. Now that you are a grown

man, I tell you my faults. I

used tobacco snuff. It jump-started my day. I used to have a flame in

the neighboring village. She was loyal. I used to visit with her on

the horse back. I would be gone for days. In my days, only the military officers, the royalty and the nobility rode on the horses.

We belong to a family of tax collectors for the

State and later the British. We commanded a great deal of respect in the villages. My

father and his father before him owned three villages. The property

whittled down because it was shared among the progeny. Our ancestors and

I did not work one day in our lives.

The house you and I lived in was the only one brick

house around. It was humongous. You don’t remember. When the workers dug

the earth to build the house, my ancestors found swords and other

accouterments indicating the ground was a battleground. Yes, life is a

battle. How you live it matters more than victory or defeat.

My ancestors owned a humongous grove in our village. My

parents told me the royal visitors passing by invariably pitched their

tents, rested, relaxed and enjoyed the cool breezy grove.

As I finished reading the letter from my

grandfather, I received a letter from my aunt on my mother's side.

I am now in the other world.

You remember me well. I took you in during your

tender years because there was a great deal of animosity and ill will

towards your family for no fault of yours. It was always about property

disputes, jealousy... Your parents did not want to raise you in that

environment. They sent you to me. So you were with me, your uncle and my

children. We had a one room school, close to my house. This is where

you learned your basic reading and math skills. We had an unprotected

well flush with the ground in the backyard. You were afraid to go near

it. My daughter fell in it, but was quickly rescued by workers. I fed

you goat’s milk. You never liked it. When your mother came visiting with

us, you complained to her about the goat’s milk. Your maternal grandmother

broke a promise to give a landed property in town as a dowry. She failed

to do it and instead gave it to her brother. Your father was very angry

and, I believe, sent robbers to your maternal grandpa’s house. The noise

in the middle of the moonless night awoke everybody in the house and

they chased the robbers, who jumped to the next house by the adjoining

upper floor (மேல்மாடி).

The neighbors caught the robbers, but they gave a slip, because they

smeared oil on their entire bodies. The police caught them and they told

the police they were directed to rob the place by the son-in-law (SIL).

The SIL was taken to the town

police station. The police saw a light-skinned gentleman of sorts,

offered him a seat and treated him with dignity. The in-laws came to the

police station and swore that their SIL had no problem with them. SIL

was released and never prosecuted. I don’t know what happened to the

actual robbers.

A few years later, my father and your maternal

grandfather graciously allowed for your family to live in the nearby

town for your schooling.

My elder aunt sent me this letter.

Dear nephew:

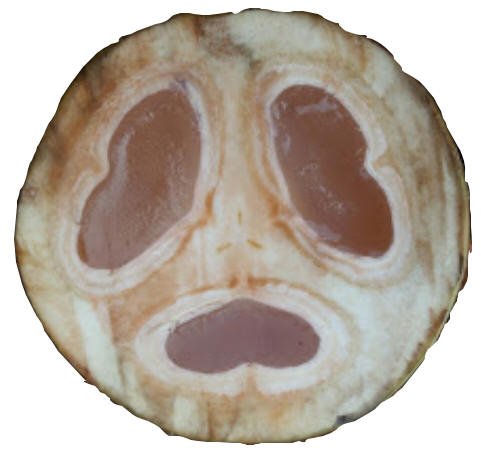

Our love for you was well known. You visited with

me, my sons and your uncle many times. You used to go to the groves and

ate nuṅku.

நுங்கு

nuṅku 1. Pulpy

kernel of a tender palmyra fruit.

Once I remember you showed up when you were about 10 . We were surprised to see you without your mother. You told us your father beat you up for no fault of yours and you went to us. Our village was about five miles. You walked all the way to our house from your town. Such a feat for child of your age. We sent a messenger to your parents telling them you were with us sound and safe. They came and got you and took you home. You may remember me telling your parents one day you would eat his shit (monetary help).. I am no more. I am enjoying life in the other world. Will write to you when I can.

My dear nephew:

Your mother and I, though sisters, were close friends. You and your mother

visited with us in my village often. I cooked for you very many

delicacies. You ate the

delicious mangos from our backyard tree.

You went visiting with my son to the paddy fields, played in the

wells and had a good time. Once my son took a clod of wet

mud from the rice field and threw it on your face while in the well. It

hit you on your face. Your eyes were blinded by the mud. You were clever

enough to wash it off from your eyes. Yet your eyes had residual mud.

You came home with others holding your eyes with the hands. I applied cooking oil in

both eyes. The idea was the mud would slid off your eyes from the

lubricating effect of the oil. You were lying flat until the last

particle of mud came off your eyes. Thank God, there was no damage to

your eyes.

Once your mother and you came to my village. You were tired and week. I took

one look at your eyes and noticed yellow jaundice. I summoned the

village medicine woman. She gave herbs for a few days. The jaundice

cleared. (It was Hepatitis A infection acquired by drinking contaminated

water.) I was glad later in years you became a pediatrician.

(As an attending pediatrician in the US, I was tested and found immune

to Hepatitis A.)

More later.

Yours,

Middle aunt

Dear grandson:

Your mother asked me whether I would allow her to

live rent-free in the house I owned in the town, so you can attend the

school. I consented to it immediately. You and your family lived in my

house from 1945 to 1953 with you going to school. I passed away soon

after your turned 3 years of age. I watched from the other world, saw

you go to another town for your pre-med qualification and later Madras

for medical education. I am glad for you. I know you are grateful to me

that I let you live in my house so you could go to school.

Son:

I was not a good father to you; neither was I a

good husband to your mother.

I plied verbal and physical abuse on your mother and you. Your brothers

somehow escaped the undeserving punishment. It is possible I became more

mature or too old. I said often that I liked

my brother’s children more than my own.

During your school years, I left home often for

weeks and months visiting temple towns up and down the country. I went

to Rishikesh in the north and Ramesvaram in the south and other temples

in-between. I once visited

Mr. Gandhi in his Ashramam. He asked me to stay and work with him. But I

did not stay with him. I visited with Ramana Maharishi many times and

stayed in Tiruvannamalai for weeks.

I was not

with you when you entered High School for the first time. I was away on

my jaunt.

I was with you, when you went to check the list of

admissions to medical college in 1955. I was glad I went with you. Your name was

on the list.

Dear classmate in the medical college:

You were a humor monger in the class. You

remember Urine Iyer, Professor of biochemistry. He was famous for

diagnosing illnesses just by looking at the urine. And thus his name,

Urine Iyer. He had no tolerance for students who talked during his

lecture. He was as fiery as the Bunsen burner. He would say to the

talking student: “Up you stand and out you go.” A dreaded phrase. There

were many students, ejected from the class. Once a bird flew from

outside, sat on the sill and chirped. All the students turned their

heads to the chirping bird. You did too. You did something more and

said, “Up you stand and out you go.” The class broke out in laughter.

The lecture hall shook. The professor was pissed off, did not brook the

bird, your humor and the laughter. He dismissed the class at once.

Thanks for the break, my friend.

The interference by students did not abate in his

class. The

female medical students sat in the first few rows of lecture auditorium

with staircase stadium seats. The mischief mongers threw paper balls on the

female students, when Urine Iyer turned his head to the blackboard. No

one was caught in the act. But you were not one of them.

Once (1957) the professor of public health was talking

about old age and its problems. She posed a rhetorical question to the

student body: “What would you do with the old people?” No student

answered the question. You stood up and said, “Madam professor, I will

put them on a rocket and send them to the moon.”

( 2018: I am 81 plus; please don't send me to the moon.)

We all knew you did not mean it. Then there was no rocket capable

of transporting people to the moon. But it had the effect of humor on

the class. The student body laughed in paroxysms. Madam professor

thought it best to dismiss the class. Of course, you were not punished.

The professor probably enjoyed the joke for joke’s sake.

You remember some boys smoked cigarettes and the

ladies avoided going near them because of the smell of cigarette smoke

clinging to the white coats. One of them standing behind the female

students in the medical wards in case presentation and moderation by

Professor ALA, the smoking students dropped the cigarette butts into the

pockets of white coats of the female students.

You remember another friend of yours. He was a

brilliant student and yet failed in medicine case diagnosis and

presentation for no fault of his. He might have failed because of the

examiner’s prejudice against his twice-born status. He became a famous

surgeon.

I visited with you in NYC and stayed in your

house with my wife for a few days. My wife was impressed with your

bathroom, clean and immaculate like the operating room.

When we went home, we built one for ourselves.

Professor of physiology sent a letter:

Dear student:

You were an average student in my class. The

physiology examination had two sections. You mixed up one section with

the other and wrote section one answer in section two. The answer was

correct but was written in section two. I discovered your

unintended error and gave you a pass.

(Thank you professor for your kindness.)

Professor of medicine:

Dear student:

You were an average student. You thought and spoke on your feet. Remember, I asked questions about the complications of diseases on the ward rounds. The smart ones rattled off the complications. I asked anything else. You said, "death." Yes, that was the ultimate complication of life on earth.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

June 23, 2018 Your mother.

Dear son: You are 81 now and in good health, considering your age. Yes, you remember I died when I was 89 years of age. Thanks Bhedappavu

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Dear Medical student:

I remember you as a student in our high school