சக்தி விகடன் -

12 Jun, 2010

Part 1

Posted Date : 06:00 (12/06/2010)

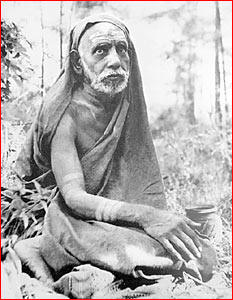

ஸ்ரீரமண மகரிஷி

Author

![]()

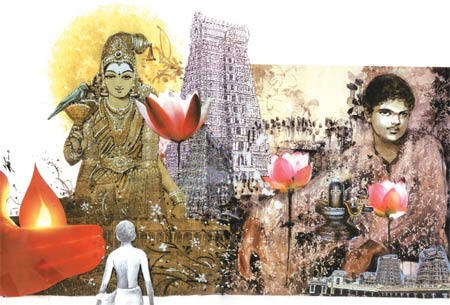

Madurai City of Mīnākṣi

Amman Temple

Venkatraman and Nagaswamy in Madurai

Madurai is a big city. Venkatraman and Nagaswamy from the village sought

refuge in Madurai, which they explored well. They were surprised to see

people everywhere.

Venkatraman went to two schools: Scot High School first and later

American Mission School.

Their house was in Sokkappa Nāyakkar Street near the South Tower. The

tower was visible from the upper floor of the house.

The town was busy with bullock carts, tongas, mobile sweets stalls…

The temple’s geographic size, the paintings, the idols, the festoons and

colored lights made everyone feel Madurai’s greatness.

Mīnākṣi

Amman Temple held daily festivities. Many other temples were near

Madurai Temple. Azhagiya Perumāḷ

Temple built on the namesake mountain enjoyed popularity among devotees.

Sweet Poṅgal

Prasādam

served there was ambrosial.

Venkatraman went for Prasada to the temple where the presiding deity was

Kaḷḷazhagar

with people knowledgeable with Abhiṣēkam

Ārāthanai

(Ritual ablution and worship). When the passel of devotees returned home

in the night, the burden of carrying the ambrosial Prasada fell on the

head (literally) of brawny Venkatraman at their behest. He with a

painful wry neck wobbled along in the dead of night carrying the load on

his head. He put the load down and discovered his wry neck was swollen

and hurting.

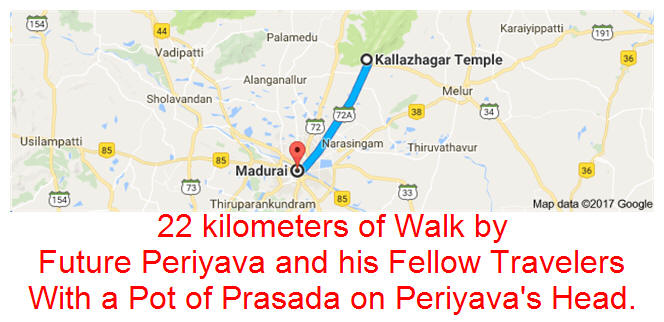

From Kallazhagar Temple to Madurai

Venkatraman was harsh on himself thinking, ‘I desired for Prasādam,

is it not so…Bhagavan made my neck suffer pain. Suffer, suffer to the

full extent.’ Again, he carried on foot the mother lode of Prasādam on

his head to Madurai. The workers, the ritual priests who performed the

worship and Venkatraman shared the Pongal.

Older brother Aṇṇāsāmy

and his peers were the playmates, as Venkatraman was house sitting. When

Aṇṇā

went for his studies, Venkatraman with his friends went to Māriammaṉ

temple for swimming (in the temple pond). If his friends were not

available, he went around the temple. He had a liking for all things

except studies. Studies are important, if one wanted to be gainfully

employed as a clerk and satiate his hunger from the salary. When his

elder brother went away to play, Venkatraman read Periyapurāṇam laying

around among other books. The written style was hard, though he found

the content fascinating.

He

wondered, ‘What is this? As a tender child, he sang poetry.’ ‘'தோடுடைய

செவியன் விடையேறி யோர் தூவெண் மதி சூடி...'

(=

The ear-ringed One riding a bull and wearing a pure white moon…’) How

could Tirugñāṉasambandar ever sing like this? Why did Śiva and Pārvati

appear from nowhere and offer milk to a child? How wondrous, what a

blessing!’ He read the poem many times and became immersed in ecstasy.

He

wondered, ‘What is this? As a tender child, he sang poetry.’ ‘'தோடுடைய

செவியன் விடையேறி யோர் தூவெண் மதி சூடி...'

(=

The ear-ringed One riding a bull and wearing a pure white moon…’) How

could Tirugñāṉasambandar ever sing like this? Why did Śiva and Pārvati

appear from nowhere and offer milk to a child? How wondrous, what a

blessing!’ He read the poem many times and became immersed in ecstasy.

A wedding for the daughter.

Śiva Yogi stands at the entrance. He asks, ‘What is special today.’ The

father invites the Yogi inside and tells him exuberantly, ‘My daughter

is getting married.’ He calls his daughter and prospective son-in-law to pay homage

to the Yogi. Yogi offering his blessings to the couple, notices the long

tresses and says, ‘O my, What long tresses. If you give me the tresses,

I will plait and wear them as sacred thread.’ The father thinking there

is no blessing greater than making an offering to a Śiva Yogi, sat his

daughter, shears her head completely and offers the tresses to the Yogi.

Śivayogi was none other than manifest Śiva. Śivayogi disappears; Śiva

himself offers his appearance; the bride’s head appears full of tresses

as before. All the people around the bride received great boons.

Venkatraman’s eyes were welling with tears. What a condition of the

mind! The mind which keeps nothing for itself. How did this ever happen

to them?

An order to graze the cows. Chandēsvara

Nāyaṉār

grazed the cattle. He seated a

Śivaliṅgam

on the grassland. He milked the cows and used it for ritual ablution of

Lingam. He had no mental satisfaction. He did another ritual ablution.

He milked all the cows and used their milk for ritual ablution. The

owners of the cows complained loudly about lack of milk.

One day, his father eyed him from a hiding. He became angry at him milking

the milch cows for abhisekham. He caned and pushed him. The son put up with corporal

punishment.

‘What is this? Does this constitute God? Is this Śivaliṅgam?’ Saying

such blasphemous words, the father raised his leg to kick the lingam but

the son immediately landed an axe heavily on his leg. The leg broke off

and hit the grassland.

Though you are my father, I will tolerate killing by you. But, no one

may abuse my God. Though he is my father, I will punish him.’ Saying

such words, he rose in anger.

Śiva

made his appearance and made him calm and composed.

Of all the stories Venkatraman read, the story of Kaṇṇappa

Nāyaṉār

was wonderful and impressive. The hunter named Thiṇṇaṉ

chased a wild pig, killed it, cooked it and shared the meal with his

friends. Something up in the mountain drew him from dinner guests. He

saw a Liṅgam. “Are you not alone, you must be hungry.” Saying such

endearing words, he embraced the Liṅgam and brought the flesh of the pig

and water to feed the Liṅgam. He transferred the flowers from his head

to the top of the Liṅgam, poured the

water from his mouth on Liṅgam as ritual ablution, placed the meat

before the Liṅgam and begged

Śiva,

“Eat, Eat.”

I

Next day, the priest in charge was shocked to see meat before the

Lingam. He cleaned up the place scolding the unknown server of meat. Later, he

performed Pūja

with Bael leaves and left the site. A little while later, Thiṇṇaṉ came

and said to himself, ‘What is all this leafy garbage. Where is the meat

I served you yesterday? Did

Śiva

eat the meat? Or someone else took it away.’

It

does not matter. I will bring the meat again.’

So, it happens. Nonplussed and irritated Śivācchāriyār

cleaned up the

place. Leaf-worship happens. ‘Who put these leaves again?’ Getting

upset, Thiṇṇaṉ clears the leaves and goes away to bring meat for liṅgam.

There happened a wondrous event.

It

does not matter. I will bring the meat again.’

So, it happens. Nonplussed and irritated Śivācchāriyār

cleaned up the

place. Leaf-worship happens. ‘Who put these leaves again?’ Getting

upset, Thiṇṇaṉ clears the leaves and goes away to bring meat for liṅgam.

There happened a wondrous event.

‘Who in his right mind serves meat to Śivaliṅgam?’

Entertaining such thoughts, the priest was lying in wait to catch the

perpetrator of the forbidden act. Blood

was pouring out of one eye of Śivaliṅgam.

Thiṇṇaṉ, thinking the remedy for the bleeding eye is another eye (an eye

for an eye), enucleated his own eye with the arrow and placed it in the

eye socket of the Liṅgam.

The other eye also bled.

‘I have the cure in my hands.’ Wait, if I enucleate the other eye, I

will be totally blind. How could I apply the donor eye in the place of

the bleeding eye?’ Entertaining such thoughts, with no hesitation, he

raised his leg and placed the big toe, where his eye had to go. He got

ready to enucleate the other eye with his arrow. A hand shot out from

the Lingam with a voice saying, “Stop Kaṇṇappa”

and prevented him from going further. The title ‘Kaṇṇappa'

came from the mouth of

Śiva.

The Brahmin priest witnessed this wondrous event.

When Venkatraman finished reading the story, he placed the open book on

his chest and remained mesmerized. Before God, there is no caste, no

hierarchy and no

difference. Those with true love in them are the highest. There is no

need for an ostentatious ritual worship.

God takes in his good graces those who self-dedicate and

surrender to Him, by expelling ego. To them he presents himself in a

vision of

Ṛṣapārūḍar

(ரிஷபாரூடர் = the Rider of the Bull = Siva).

‘Is it possible, could I give myself to

Śiva

(dedicate my body, mind and soul to Siva)?

Whom do I ask? God gave vision of himself to 64 Nāyaṉmārs.

Would he give me his vision? What am I doing? Simply going to the

temple, apply kumkum and ash on my body and return home.

Have I ever looked at God with an intense concentration? Have I ever

opposed my palms and ask for any boons? There was a mad rush in all

places. Sloth and slumber afflict me. Why did I not get involved?’

When fatigue came over him and he found himself helpless, he felt

death experience.

The impact of Periyapurāṇam and the death of his father: They gave him fear

he was incapable of doing anything. Who am I? is the question that arose

in the mind of a sixteen-year-old. Venkatraman thought assiduously about

death.

He experienced death, he experienced death. What is known is knowledge;

that he knew. That when attained gives loftiness; he attained that

loftiness.

After he experienced what death is, Venkatraman did not know what to do

next.

-

தரிசிப்போம்...

Let us have a Darśan

படம் சு. குமரேசன்

Photos: S. Kumaresan

·

சக்தி விகடன் -

12 Jun, 2010

part 2

·

தொடர்கள்

Posted Date : 06:00 (12/06/2010)

The personification of compassion is Ramanamaharishi.

Author: Sarukesi

Lakshminarayanan describes an exciting event that took place when Periyava

came to Chennai.

The Hindu Newspaper’s author J. Kasturi invited Periyava to Chennai.

Periyava asked him, “Why should I go to Chennai?”

“It was a long time since you came to Madras. I wish your footprints

fall on Madras.” Such was his compelling argument.

On his invitation, Periyava came to Chennai. Gindi was on the outskirts of

the city. There, Kalki Sadasivam, Sudesmithran, Srinivasan…erected

plantain trees, had Pūrṇa

Kumbam ready and waited to invite Periyava.

When Periyava arrived, they

extended the usual reception and honor with the burst of firecrackers

and took him on a procession.

Then, Kasturi requested Periyava to visit ‘Hindu’ office. Periyava

visited all departments in the office, spoke to the employees and blessed

them. The employers were all happy. Srinivasan requested him to drop

into the office of Sudesmithran. Yes, he went there too. Sadasivam took

him to ‘Kalki’ office too.

On

that occasion, he walked in a procession in Mylapore with his retinue.

Devotees walked behind him.

On

that occasion, he walked in a procession in Mylapore with his retinue.

Devotees walked behind him.

Then, there was a proposed conference of Drāvidar

Kazhakam in Māṅkollai.

The party volunteers assembled there. They were waiting for Periyār.

The people accompanying Periyava were afraid that the Davida Kazhakam

volunteers may talk with fury and bring old disputes to the fore. They

worried about what to do with that eventuality as a possibility.

E.V.Rā.

Periyār

arrived at the conference. He enquired with the volunteers, ‘What is the

matter? Why all the excitement?’

They all said, “Kanchi Sankarachariar is in town going on a procession.

The volunteers say they want to show the ‘Black Flag.’ We are waiting

for your

permission.”

Periyār said, “What, Black Flag. Nothing of the sort. Let the

Sankarachariar procession proceed without any molestation. Don’t block

him. Don’t show him the Black Flag. First, let him pass.”

Periyava’s procession with no interruption came to the Sanskrit College.

No untoward incident took place.

When told to Periyava, he smiled and said, “Kamakshi will take care of

it. Did I not tell you that before?”

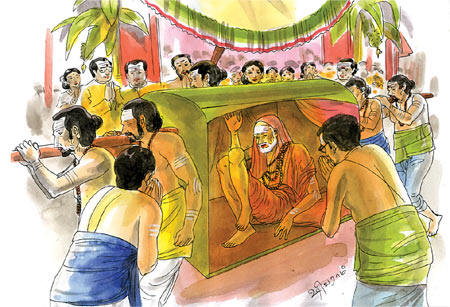

Periyava usually travelled by ‘Mēṉā’

(= light coach). Like the palanquin, it was light, carried by four

people. Periyava sits huddled inside.

huddled inside.

Once in Drāvidar Kazhakam gathering, a person was furious saying, ‘He

alone travels by palanquin. Others had to carry him. Aren’t they people?

Why can’t he walk?’

That reached the ears of Periyava. Immediately he got down from the Mēṉa

and walked. The people said, ’Periyava, please do not listen to him. It

is our blessing and good fortune to bear you in the palanquin on our

shoulders.’ The devotees begged Periyava to get into the palanquin but

he refused. Periyava said, ‘what they say is true. This recluse does not

need a palanquin.’ Since then, he refused to travel by Mēṉā.

Periyava, rain or shine, stayed where he could and then went on foot,

come good weather. No matter the distance, he walked. He never gave up

the mental resolve.

|

-

தரிசனம் தொடரும்

Darśan will continue. |