Sadhu and His Peregrinations

By Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

There were three

brothers, a doctor, an engineer and a wanderer. The first two stayed in one

place; the third one knew not where his next meal, his next transport, his

next bed, his next travel companions would be. You might call him a troll,

though intelligent, observant, compassionate and almost divine. He is a

polyglot with an added facility to communicate with animals: He speaks

Animalish. He is richly endowed with biomagnetism, with which he endears men

and animals. He calls himself the Faunal-Lingual as opposed to standard

nomenclature, whisperer. He can do all the animal noises known to man and

animals, that too with intelligence and understanding. He knows all the

nuances of animal-speak. Besides that, he could ferret out their likes,

dislikes and other myriad emotions of man and animal, which humans never

care about and willfully ignore to the detriment of man and animal. He knows

his human and animal psychology in its complexities.

Faunal-Lingual = One who understands and speaks the language of fauna.

We all talk to God, animals, preverbal babies,

comatose relatives in the hospitals, and ourselves. We know they may listen

and understand, and yet we speak to people afflicted by alalia and other

neurological conditions, not expecting answers. We are very amusing in our

speech with animations when we talk with babies; it always becomes clownish,

and something funny to look at but is deeply satisfying in the parent-child

bonding, interaction, and relationship. The baby talk has its own

vocabulary. As we gabble, the baby burbles to our immense satisfaction.

Faunal-Lingual is a tight-fisted traveler. His

needs are very few and so his travel Rupees if any goes a long way. He is

not afraid to camp by a stream, in a shed, railway station, public park,

low- budget rental, cave, temple…, anywhere he could rest his head and

stretch his body. A stray dog got on his scent and followed him wherever he

goes. The dog learned to stay away from people and animals when they do not

like its presence.

The

fortunetelling parrot

As he is walking down Bazar Street, the

fortunetelling parrot begs his attention. The man is sitting on a mat with

the cage and the pictures of Siva, Vishnu, Lakshmi, Kali, and Durga. The

handler upon payment from the client feeds the bird a pumpkin seed, which

the bird adroitly shells to eat the meat. The bird keeper calls the bird, to

which the bird answers in the language of the keeper. It picks a card from a

pile and hands it over to the fortune teller, who rewards the bird with a

pittance of ripe mango. The bird saunters back into the cage on its own

accord, and the gate shuts behind it. The soothsayer reads the card and

advises the fortune seeker. The cards have information about job, love,

marriage, fertility, education, friendship, inheritance, rewards, death,

birth, pilgrimage… He advises the client to go to the temple to seek

remediation from god or goddess.

With permission from the bird keeper, the Sadhu

speaks with the bird.

Sadhu: How are you doing? Do you

like what you are doing?

Bird: I was once a free bird.

This cruel man cast a net with nuts, seeds, and raisins. I swooped down from

my perch and ate the goodies. When I had my fill, I could not escape and fly

out of the net. I am forever separated from my mate. The man clips my flight

wings and renders me flightless. During my training sessions, he had my foot

tied down to the gate of the cage. When I am not working, he keeps me in the

cage. I hate the confinement of the cage, love to fly away and live with my

own kind in the wild. The keeper treats me well, cleans my cage, talks

kindly, and feeds me well. I am getting adjusted to my lonely existence.

The Squirrel and the nuts

He talks to the

three-striped palm squirrel, which is not afraid of him. He picks up a squirrel

and gently runs his fingers on its back. He loves that gentle human touch.

Squirrel: My

kind has raucous arguments with the dogs, cats and children… The larger animals

seem to want to molest and or sometimes eat us. The children use slingshots to

kill or maim us. They sometimes use nuts as projectiles. That is sick. Thank

god, we can climb up the trees before they can catch us. It was good living in

the forest, where the food was plenteous. Now that we have migrated to towns,

many of my kind die from run-over by cars.

Sadhu: Yes, that is the

hazard of living in towns. Do you know that you are among very few animals

which descend down the tree heads first? You can spot the danger on the ground,

turned around and go up the tree. Do you

have any problems?

Squirrel: Yes,

the buried nuts sprout as the spring comes along. We starve and eat buds, which

is not satisfying. I need to eat tons of nuts to breastfeed my blind, toothless

and naked babies. I am happy to see the teeth erupt in the young so they can

eat nuts like me. I heard of Rama who stroked his fingers on our species and

gave us the three stripes for building the bridge to Sri Lanka to rescue his

spouse.

The Donkey and

the Onerous Work Load

In towns and villages, it a common sight to see

donkeys carry bales of laundry. The Sadhu sees a donkey and a Dobhi

(washerman) near a river. As the Dobhi is mercilessly beating the clothing

on the flogging slab of stone, wringing it, dipping it in the detergent

solution and then again beating it to death, the Sadhu picks up a

conversation with the donkey.

Sadhu:

Dear donkey, how are you doing today?

The Donkey:

Fine, thank you. As good as I can be. Thank god I am resting, while my

master is slogging the piteous clothes to death on the stone. A small

percentage of clothes are torn from the severe punishment they receive from

him. You see I just finished eating tender grass he brought. You came right

on time. I am unlike the cows which need their time chewing the cuds. For

nutrition, my boss gives me measured quantities of hay grain, salt… I have

no complaints on that score.

Sadhu:

You must be a happy donkey.

The Donkey:

I am not happy about the other washerman who mistreats his beast of burden.

He overloads my friend with a heavier bale of laundry, which I assume could

break its back. It just simply does not move or simply collapses on the

ground. It would not budge until the burden is lessened. Once it saw a snake

and would not go forward, went backward, kicked with the legs and raised

dust. Its master beat my friend up because he does not see the snake.

Such a stupid person

serves as its master.

I am very accommodating to my boss because he

knows and understands me. We go side by side. I am like an equal partner

with my boss and part of the family. I even play with his children, who

taught me to play ball with my feet and muzzle. I am a quick learner. Once I

brayed when there was a scorpion in the ballpark. My master appreciated my

swift thinking and gave me a banana.

My friend had a sore on his back and told me about

it. I grabbed the shirt of my master’s child and showed him the sore. At

once, my boss persuades the other man to take my friend to the Donkey

Sanctuary for treatment.

The Crested Serpent Eagle (Spilornis cheela) and the Sadhu

The Eagle was flying over the canopy of the forest, as the Sadhu was

half way towards it. The bird of prey enjoys eating small snakes, rats,

mice... He flies over villages and cities, swoops down and steals snacks

from the hands of children. (The author was one of its victims.) As the

Sadhu is walking on a grassy path by the fields, the bird, seated on a rock,

is tearing the flesh of a field rat it caught recently. The Sadhu rests

under a Banyan tree near the rock and waits to have an audience with the

king of birds. The Sadhu approaches the bird, which flutters its wings but

stays put, knowing a swami is a man of peace.

The Sadhu:

Greetings, King of birds. How do you do? You seemed to have had an excellent

sumptuous meal.

The Sadhu:

Greetings, King of birds. How do you do? You seemed to have had an excellent

sumptuous meal.

The King of Birds:

Sadhu, dispense with your niceties. You are a man of peace and a vegetarian.

What do you have in common with me?

The Sadhu:

You are right. One of your distant cousins serves as the mount for Lord

Vishnu, whom I worship as my God. That is the connection.

The King of Birds:

O I see. Last time I heard from my cousin Garuda, he told me it dropped The

Lord off in Pune when a snake on the ground made him hungry. The stranded

Lord had to walk all the way to Kasi on foot.

The Sadhu:

And yet the Lord did not fire him from his job but kept him. Such is the

glory of a forgiving Lord. What is this fuss about your being the King of

Birds? Do you hold court? How do you treat your spouse?

The King of Birds:

Watch your words, Sadhu. You should not be too inquisitive with the affairs

of the King. If you get too close to the king or the sun, you may be burnt;

if you are too far away, you may be frozen. Keep the right distance.

The Sadhu:

O King of Birds, I hear the words of wisdom loud and clear.

The King of Birds:

My spouse and I build and defend the nest, and my spouse incubates the egg.

The nest is perched high on Indian-Laurel tree. We dine on live snakes and

lizards we see from our high perch.

He walks by the peanut fields with mounds of

harvested fresh and crunchy raw peanuts, takes what is given by the farmer

and feeds the birds and monkeys on his travels.

He sports a beard and wears clean clothes, which he washes in running

streams and ponds. When he is in town, his very visage invites attention

from men, women, and children, who know he is a peaceful mendicant. They

help him with money, food, and change of clothes. They feel they are blessed

by helping him and by his presence. His sartorial splendor is limited to his

loincloth with a bare chest.

As he is walking down the dusty narrow lanes

of the slum dwellers of a town, the ground-pecking chickens and small birds

greet him but are too scared to stay their ground. Further away there are

the green meadows with geese, ganders and goslings. The front of the huts at

the entrance is shiny from daily cow dung treatment of the floor and

decorated with Kolam, decorative figures and Mandalas

drawn with rice

flour. The ants in the neighborhood come foraging for the rice flour.

The

Sadhu, the chickens and the Gander

The Sadhu tells the

chickens not to scatter on his approach but to sit in a semicircle and

have an audience with him.

Sadhu speaks in Fowl language. Why do you

cackle and scatter as people approach you? One less timid chicken: We

are small, you are big. We are not afraid of the small birds. We have

seen the foxes from the woods come and eat us. And so do the people. We

are too heavy to fly like the kites; our wings are very modest. People,

snakes, and other animals steal our eggs. Most of my fellow birds do not

even defend when the housewife simply swipes our eggs from under our

bellies daily. Some people do not like brown eggs. Some of us are

hatchlings from them. The man of the house clips our beaks so we can’t

peck the hands of the housewife with our sharp beaks.

Sadhu: That is the fate of

the weak and the powerless. That is your lot. Live for the day and leave

the rest to fate.

He goes to the pond adjoining the green meadow. On

the way, a gander honks, pecks on his foot and walks towards a deep hole.

The intuitive Sadhu peeps into the hole lighted by the midday sun and sees

fledglings flapping their tiny wings at the bottom and emitting muffled

honks. At once he plunges his hands into the hole and rescues five goslings.

He goes to the pond adjoining the green meadow. On

the way, a gander honks, pecks on his foot and walks towards a deep hole.

The intuitive Sadhu peeps into the hole lighted by the midday sun and sees

fledglings flapping their tiny wings at the bottom and emitting muffled

honks. At once he plunges his hands into the hole and rescues five goslings.

Sadhu: What happened?

Gander: I

babysit for the crèche, when their mothers are away. The raucous goslings do

not follow me but wander into the hole.

Sadhu: Do you have any

enemies?

Gander: Yes,

the village dogs. They always pick quarrels with us. They keep chasing us.

There is no peace when they are around. Children and adults are fun to have

around. They feed us many goodies. (The dog following the Sadhu stayed far away

from the gander.)

The Sadhu, the Cow, and the Cobra

Once he is traveling on the road by a meadow. The cows are grazing

peacefully with the calves by their sides. The dog stays away at a distance.

He stops and picks up a conversation with a cow in the language of the cow:

Cowlish.

Faunal-Lingual: How are things

with you, cow and calf? Are you all happy?

The cow: We are as happy as it

could be. We are sometimes bothered by the coyotes, foxes, stray dogs, feral

dogs, cheetahs or any other carnivores. The cattle owner treats us well. He

does not sell us to the abattoir, though we saw the butcher begging him to

sell us in our old age when we are no longer yielding milk or bearing

calves.

As I was

talking to the cow in Cowlish language, a cobra appeared nearby and demanded

milk from the cow. The cobra threatened to bite the cow if it did not meet

its demands. Faunal- Lingual came to the aid of the cow and spoke to the

cobra.

Faunal-Lingual: (Speaking in

Cobranese) I assure to give you a pot of milk if you do not bite the cow,

its calf or me.

The Cobra: Thank you

Sadhu (a man of virtue and peace), I look up to Ganesa, Siva, and Krishna,

who all love the cows. Once I was in a stampede of a herd of cows. It was by

the grace of gods, I escaped injury or death. I will be on my way if you

give me a pot of milk.

The cow was anxious and

wondering what transpired between the soft-spoken Sadhu and the cobra. The calf

drew itself beside the mother, stopped grazing and looked at the baleful eyes of

the cobra with a dancing hood.

The polyglot Sadhu sported

benign eyes of the cow and the calf, which at once knew that they were safe.

The sadhu shifted his linguistic gears and spoke in Cowlish, which the cobra

did not understand. Cowlish = Like

English, language of cow is Cowlish.

Sadhu:

In Cowlish. Dear cow, you and your calf are safe. I will bring a pot and

please let me milk you, so the cobra’s needs are met.

The cobra had its fill of the milk and promptly slithered away in the grass,

thanking the Sadhu and the cow. The cow and the calf regained their

composure and thanked profusely in Cowlish. The calf was babbling in Cowlish

about the potential disaster that never came, which the Sadhu understood.

The cow wanted to give the Sadhu something for his

life-saving effort. It offered a pint of milk so he can quell his hunger

until the next meals. The cow yielded a pint of milk, which the Sadhu boiled

and drank.

The multilingual Sadhu was back on his

peregrination. He was convinced that even the most poisonous and vicious

being can be persuaded to give up its or his evil ways when the right path

is shown. But he had a lingering doubt clinging to him.

Another day, another time. By happenstance, he walked into a sylvan forest

where carnivores roamed. There were goats, sheep, elephants, tigers, and

lions. Enough ruminants in the jungle satisfied the palate of the

carnivores. The deer and antelopes were bouncing and leaping all over the

place. There were many fruit-bearing trees in the wilderness. It was the

first time he savored many fruits in his life. He lived in the forest for

some time living on fruits, roots, herbs and edible leaves. It was very

satisfying.

The Honeybees and

the Sadhu

As he is sitting and meditating under a tree,

something is dripping on his head and face. He looks up and sees a turgid

honeycomb. By this time his loincloth becomes wet with honey drip puddle on

the forest floor. A few bees came over to him and talked to him.

Honeybee 1: Hello Sadhu! Did you know that South Asia was the place

where honeybees originated?

Sadhu: Thanks for the

information. How is life in the forest?

Honeybee 2: I am the girl worker

bee building, maintaining and cleaning the honeycomb, feeding the larvae,

and caring for the Queen in and out of her sizeable palatial cell and making

honey. We live, work and die. We have the distinction to select larvae to

become queens. We feed the Queen(s) exclusively Royal Jelly loaded with

carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals secreted from the glands on

the head of the young worker bees from the time she is a larva and follow

her as she lays the eggs, one in each cell. The queen’s palace looks like a

vertically placed peanut shell. The worker bees determine which fertilized

eggs become queens and sustain many queens because they want to assure the

survival of the hive. The dominant queen rules the colony. Others die or fly

off with swarms. If there are multiple queens, the dominant queen may turn

homicidal. Sometimes the old queen may live and lay eggs until it dies a

natural death. When virgin queen emerges dominant, the mated queen is killed

by workers, and non-emergent queens are killed by the emergent queen. Virgin

queens may take off with workers in a swarm to build new hives. Virgin queen

and or old queen may make a clarion piping call to workers to fight for her.

The girls having

mother and fathers come out of fertilized eggs; the boys having mother only

0come from unfertilized eggs. You can look at the cell and know whether it

is a girl, a boy or a queen. Boy’s cell is bigger than girl’s, the queen’s

the biggest. There is no such thing as sex chromosomes in the honeybee

kingdom. The boys

with bug-eyes hang out in Drone Congregation Area, to spot and mate with the

queen. The queen revisits the area many days until her sperm sac

(Spermatheca) is rippling with 6 million sperms, which would last for 2-6

years. If the queen stays a virgin because of weather conditions, she is

dubbed as “drone layer” because she cannot beget female workers or a

prospective queen to follow her but beget only boys. The bee colony will

dwindle to nothing in the boys-only club.

By this time the worker bee becomes hungry, goes

to the beehive, has a drink of honey and comes back to the Sadhu to continue

her narrative.

Supersedure or supersession = the state of being superseded. This is

replacement of the older queen with the new queen, either done by the bee

worker or apiarists. Sometimes the beekeepers mark the difficult-to-identify

queen on its back with harmless colored dyes.

The queen lays about 2000 eggs a day. My mother is the

queen. When my mother dies the fertilized egg already laid by my mother could be

prompted to become the new queen, and she becomes my sister, the queen. Normal

boys are haploid coming from unfertilized eggs of my mother. We are diploid, a

product of fertilized heterozygous egg or embryo. We eat the diploid male bees.

As a youngster, I

worked as a nurse feeding larvae with Royal Jelly. Later, I did foraging and

making honey, sanitation work, cleaning the cells of dead bees, guarding the

honeycomb... I have odor receptors in my antennae. I can smell my sister and my

mother the queen from a distance.

We eat honey for energy and pollen for protein; this

honey-pollen diet is called bee bread. When the enemy insect invades the

honeycomb, we gang up on the insect, increase the ambient temperature for the

insect, exhale a ton of CO2 and induce heat exhaustion, oxygen deprivation, and

CO2 narcosis in the insect, which eventually dies.

The boy-drones with a fatal

attraction to the queen from other hives have all the fun before their death if

they get to inseminate the queens. The bug-eyed boys are on the lookout for the

queens on nuptial flights. The boys hang around in congregations. Once the

transfer of the sperm takes place (the sperm goes into the sac called

Spermatheca of the queen.) from the drones to the queen, the boy’s endophalus

gets ripped off mercilessly, and the emasculated drone male bee dives and falls

precipitously and instantly dies. Hey, that is nature, but it is real and cruel.

After successful in-flight insemination, the queen goes back to the hive, where

the workers remove the leftover apparatus. If the queen continues her nuptial

flight, the next paramour removes the apparatus and inseminates the queen.

Coming back to the inseminated queen by multiple partner drones, the queen has

the option to fertilize the eggs for a two to three-year period to produce the

working female bees or produce unfertilized eggs making drones.

The hive has more workers than

drones. "We girls never ever lay eggs. The lucky larva fed Royal Jelly for the

longest duration during the larval phase becomes the queen. We make that

decision who the future queen will be."

The queen goes from cell to cell laying eggs; the

larva comes out in 3-4 days and eats Royal Jelly given by the female workers.

When the pupa emerges, we close the cell with wax. The worker and drone larvae

are fed Royal Jelly for 2 days. The queen larva continues to receive Royal Jelly

until she spins the cocoon. For metamorphosis from egg to bee, the queen takes

16 days, the worker bees 21 days and the drones 24 days.

The queen lives for 3 to 4

years, the workers live for a few weeks, and the drones die soon after mating

and never ever mate with the in-house native queen. The ejaculation always makes

a popping sound.

We

concentrate the nectar and honey by repeated ingestions and regurgitations. For

the bees to make one quart of honey, it takes 48,000 miles of flying. We make

wax from abdominal glands. Girls have barbed stings, boys don’t. Queen’s sting

is not barbed. We girls die soon after we sting an intruder, a human…; the sting

apparatus detached from the body has the sting, venom sac, and the musculature

to pump the venom into the victim. The queen has no wax glands but has ovaries

and spermatheca which we working girls do not have.

The comb comes with layered

apartments. The upper cells store honey; below that are pollen storage cells,

brood-cells for workers and brood-cells for drones. The peanut-shaped

palace-cell for the queen hangs from the lower edge of the hive.

Last but not least is the

neuroactive insecticide neonicotinoids used on crops adversely affecting the

bees and responsible for CCD (Colony Collapse Disorder). This insecticide

contaminates the nectar and pollen, which we carry to the honeycomb. These

neonics cause paralysis and death of the bees.

The

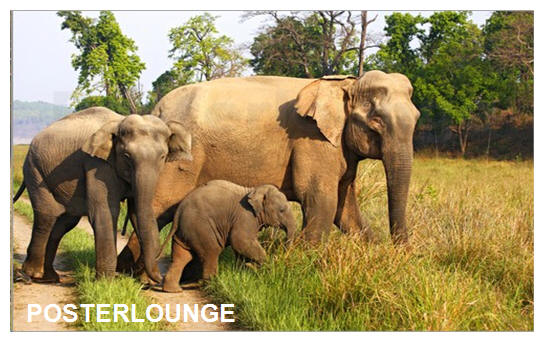

Elephant and the Sadhu

One day a female elephant

with its calf was passing by. Yes, he spoke Elephantish.

Sadhu: Hello Gaja (elephant, Elephas maximus)). How are you doing? Do you

know of any waterfall or pond for a shower or bath?

Photo: thehindu.com by Ritu Raj Konwar

Gaja: I

know of a clean water pond, where you can bathe. I also know of a waterfall

near the lake. You could ride on me if you wish.

Sadhu: Thank you very much for your offer.

The elephant knelt on the ground instinctively and let the Sadhu climb on

its back with the dog tagging along. They reached the pond, and the Sadhu

was taking a long-sought bath. At that moment they did not notice the

tigress with cubs lapping up water about a quarter mile away. The tigress

saw lunch in the elephant calf and approached the calf, which by instinct

went under the body of its mother to hide. The mother elephant charged,

trumpeted, picked up the tiger by its trunk and flung it into the pond right

around the Sadhu taking a bath. The tigress was closing in on him.

Sadhu: In Tigerish. What is your intention?

Tigeress:

I am hungry. I want to eat you.

As the tigress was talking with the Sadhu, a croc

surfaced from the depths and heard the conversation. The croc liked the

Sadhu and lowered itself enough to let the Sadhu climb on its back. The croc

previously swallowed a small deer, and that may be why it was so obliging to

the Sadhu. Or it could be Sadhu’s charisma and message of peace which

appealed to the croc.

The Croc did not talk to the tigress but splashed

and whipped its tail so hard, the tail almost broke the neck of the tigress,

which knowing its vulnerability in the water against a croc swam to the

waiting cubs on the bank and ran away into the thick foliage. The Sadhu

thanked the croc in Croconeese dialect and rode the crock to the opposite

bank.

The Sadhu bid goodbye to the croc, crossed over by

a land bridge and took leave of the elephant on the other bank and went on

his way along the bank. There appeared a herd of Indian Bison led by the

matriarch. They had their fill of life-giving water and made a retreat back

into the woods. The Sadhu approached the matriarch and spoke in perfect

Bisonese he wants to take a ride on its back on the uphill terrain.

Gladdening to hear someone speak Bisonese, the matriarch moved close to a

ledge, wherefrom the Sadhu mounted the matriarch and held on to the horns.

He held the in-curving horns in such way and moved them like the car wheel

it appeared he was driving a bison-mobile. As they were nearing a meadow in

the jungle, the hungry cubs were playing with each other and the mother

tigress. The bison did not care and were ten in number of which two were

calves. The tigress poised itself for a charge. The bison kept the calves in

the back and formed a phalanx ready to take on the lone tigress. It was no

match between the lone tigress and a phalanx of sturdy bison.

The

Sadhu shouted to the tigress and told it to take on smaller animals. The tigress

took off from the meadow with the cubs. He had to spend a hungry night with

growling cubs. The bison took him to the plateau of the mountain range and

dismounted him. As a parting gift, the matriarch commanded a lactating mother to

yield milk to the Sadhu, which he accepted gladly.

The Sadhu and the Mountain Tribe

The Sadhu was enjoying the scenery from the top of

the mountain. There were goats and sheep tended by shepherds. It had been a

long time since he saw human beings. There were hutments with children

playing with young animals. They are a community of about a few hundred

people. They spoke hill country language of which he was very familiar. They

do not marry close relatives, and the prospective man and wife are several

degrees separated from each other. They are a robust hill tribe. They

invited him in their midst and offered him all amenities they could afford.

He learned from them they communicated with the animals, departed ancestors,

and mountain spirits all the time. They pointed to the sky as the abode of

their departed ancestors. They were lactovegetarians; they never ate meat

from the sheep or goats. They wore wool from shearing and skin from

naturally-dead animals.

A mountain stream nearby supplied them with water.

Fruit trees of all kinds were all around. Fresh and root vegetables, herbs,

and milk from the sheep and goats were their daily staple.

Carnivores were a problem.

Burning torches kept the carnivores at bay, and they retreated into the

jungle, never to come back again.

When a ruminant dies, they took the skin and cast

away the carcass at the edge of the settlement so the carnivores may eat it.

They never lost a living ruminant, a friend, a relative or a child to a

carnivore. They thank their ancestors for watching over them.

The Sadhu stayed with them for six months before his departure. They

worshipped the elements: water, fire, earth, sky, and ether. Lightning and

thunder are their other gods bringing them much needed rain. Their huts are

made of a central pole of sturdy wood with the bamboo poles forming the roof

and the walls, all tied with coir. The wall and roof cover was a thatch made

of straws, Palmyra leaves…all brought from the nearby forest foothills. The

roofing is compact and impervious to water.

They worshipped hills, trees, and animals. The

Sadhu introduced to them the concept of a monistic God, with many names and

forms, both animate and inanimate. He called that monistic God Isvara.

They present him a sheep wool coat to ward off the

chill of the night sky, as he takes leave.

The Sadhu and the Thuggees

The Sadhu walks down the mountain and reaches a

village populated by thugs (Thuggees and Dacoits) whose profession is to

steal from and kill the hapless. They are the most dangerous. They kill in

the dead of night or broad daylight and bury the remains deep into the earth

and keep the belongings. These thugs travel in threes, fours or fives, gain

the confidence of the fellow traveler(s), kill them gratuitously and take

their belongings. One thug distracts the traveler, the next two hold the

feet and hands down, and the fourth one applies the ligature around the neck

and tightens it until his life-breath ceases to move and his soul is taken

away to the netherworld by the minions of Yama, the god of death. The

signature act is killing by ligature. The village is their home base. They

may travel several hundred miles from their home base and return after a few

months of rapacious and murderous spree. The loot, which they don’t keep on

their persons, is sent to the village through known messengers and partners

in crime. They were never caught red-handed and always remain empty-handed

except for the ligature. Often they bury the stolen jewels deep in the

forest by natural landmarks, only they know, away from the prying eyes. They

kill even the most destitute because killing is their calling. They kill no

one in the village itself: That is the honor among these thieves and

killers. In those

days, people travel alone or in small groups to places of pilgrimage. Many

lost their lives this way, and there is no way of knowing how they

disappeared. They somehow separate the individuals from the group and kill

each one of them and take their possessions. The religious heads akin to

Pope never travel alone; they have a retinue of guards with weapons, cooks,

attendants, horses, elephants… They travel safely.

This is the way Acharyas (prelates) traveled in those days. Here is how

Sringeri Guru Narasimha Bharati traveled from Sringeri to Ramesvaram on

January 23, 1868. Source: Sringeri Mutt.

|

Three Biradaris of

horses.

|

100 Brahmins

|

100 Sudras

|

|

83 troops

|

10 daggers

|

25 Pikes

|

|

2 elephants

|

2 Palanquins

|

50 cows

|

|

2 Tonjons

|

8 Umbrellas

|

25 muskets

|

|

6 Chamaras

|

20 swords

|

10 horses

|

Birādārī = Caretaker, caste,

brotherhood, community, kinship, fraternity.

Tonjon = an open sedan chair used

in India and Ceylon and carried by a single pole on men's shoulders.

Chamara =

Tanner. The Sadhu

walks into the village. Everything appears peaceful. That peace and quiet

were disturbing to the polyglot. Everything is neat and clean as a

prosperous village would look for an outsider. Something is up. What could

be behind that enigmatic silence of the villagers? The Sadhu has nothing

worthy on him and gives away his last possession, the wool coat to a

villager as a gift. He satisfied the first condition: Shed all your

belongings. How could he meet the second condition and live? Children do not

cluster around him. They have been told not to befriend a stranger. The

adults watch him go down the streets with glum faces. Someone offers to

travel with him. He accepts his offer knowing full well the jig is up. How

is he going to escape with his body and soul from the thug’s ligature? Even

if he refused the thug’s generous but murderous offer, the thuggee would

trail the Sadhu surreptitiously till death’s door. The Sadhu’s fate is in

the hands of a professional killer- thug. Is it really so? Could there be a

divine intervention? Could the Sadhu turn the table around to his favor? The

wheels are turning in his cerebral mantle. Sadhu is the holy man; the thug

is the animal-man, which is an animal in human form. A man who talks to

animals and transforms them into a human dimension now faces a human in

animal form. That is the paradox of life and living. A man can become divine

in his outlook and behavior. How could an animal become divine before

becoming human?

They travel side by side knowing each other’s

unspoken and unrevealed intentions, desires and goals. One (Sadhu, the

divine man) has the stuff in him to transform an animal to a man and a man

to a divine; the other has the animal in him to take the life of the divine

man in human form. Is there a yet an unknown force that would set things

right? Would that force take the animal out of the thug, make him human and

put him on a spiritual path? We will see what unfolds. Would the ligature

hold its promise, though it is inanimate, uncompromising, efficacious and

less than an animal? Does the rope have a soul, as Hindus believe in the

pervasion of Soul in all things animate and inanimate? Where are his cohorts

to assist the thug in holding down the Sadhu’s limbs while the ligature goes

to work at the hands of the thug? All these things are waiting for

resolution.

The Sadhu and the thug travel by foot, cart… The

thug is always on the lookout for his brothers-in-arms, who would help him

in the commission of gratuitous murder of Sadhu. Sadhu is looking for ways

he could convert the thug from natural brute to the human domain. The divine

domain is further down the path.

Sadhu wants to cut the bonds that kept the thug in

the animal domain, while he wants to escape the fury of an ever-tightening

ligature.

The thug and the Sadhu are in the company of

pilgrims going north to a temple on the banks of Ganges. They decide they

break their journey as the dusk is falling from the skies and slowly

engulfing the earth below. The Sadhu lies down on a bed of grass in the

company of fellow travelers, who are men, women, and children walking the

path towards a divine goal. The thug could not put into practice his finely

honed skills on that night because there are kerosene lamps among the

story-telling pilgrims under the moonless night. They also lit small fires

here and there for roasting the dry peanuts in shells. They lie down in a

circle with the feet in the center and the heads at the periphery. The women

and children make separate circles.

The thug goes towards a bush to relieve himself

and unknowingly falls into an abandoned well covered with overgrown weed.

His ligature becomes loose from around his waist, caught by the twigs and

branches, travels up to his neck and practically hangs him. The sound of his

fall catches the attention of the pilgrims, who bring him out of the well

and put him on the dry grass. He talks with muffled voice, moans and groans

but does not move his limbs. The birds chirp, the crickets stopped their

chorus, the orange sun peeps out of the horizon, the day breaks and all are

awake. The embers are still alive. Sadhu and the pilgrims find the thug with

four broken limbs. There is a village medic among the pilgrims familiar with

setting fractures. He is one of the early pioneers of Puttur Kattu,

specializing in setting fractures. Medicinal leaves obtained from nearby

plants (paste from leaves of Senna tora) are applied on the fractured limbs

immobilized with sticks and twigs after the crooked limbs are straightened

by traction. The medic satisfies himself with the good bounding distal

arterial pulses after he is done with his treatment. All these procedures

are preceded with chewing and smoking of hashish by the fractured soul-body

of the thug, first the soul and the next the body. Hashish for recreation

and pain management is in plenteous supply among the pilgrims, just if such

things happen and warrant its use.

Puttur Kattu = setting the bone in the village of

Puttur.

The pilgrims and the Sadhu prepare a makeshift

gurney and carry him all the way to the temple. The Sadhu feeds him, gives

him a sponge bath and takes care of all his daily needs. And yet his

signature ligature is back around his waist, a grim reminder of his near

death experience. He smiles more often, painfully raises his hands and palms

towards heaven, and thanks the Sadhu and the pilgrims for their timely help

and generosity. The Sadhu sees a transformation taking place in the thug.

His soul has not hardened to an impervious rock. The hands raised to heavens

with the help of Sadhu are losing gradually the sinner's blood stains from

his previous egregious killings. His near death experience has lifted him

from the abyss of a relentless murderer. The soul once impervious to human

kindness is soaking up good vibrations, by which he kills the animal in him

and resurrects the dormant humanism. He has become a human and is going on a

salubrious path never-before-imagined by him or his fellow traveler.

The Sadhu and the

transformed thug stay in the temple town for six months, getting food from

the pilgrims and local merchants. They sleep where they can and eat what

they get to sustain the body. The Sadhu is ministering to his soul. Food is

for the body; ethics are the food for the soul. The thug recovers. His body,

mind, soul, speech, and behavior are changing for the better. He is now a

new person, ready for the ethical path free of ten afflictions of man. His

body is back to its old self and his wretched soul transformed into a new

self with vigor, beauty, and grace. What else can you ask for from this

degenerate soul blossoming into a flower of compassion, inner strength, and

empathy for the fellow human being? He could be the messenger to his village

of dead souls and thriving flesh. One flower makes no spring. That is the

beginning, and a bed of flowers and a garden is in the near horizon when his

transformation becomes endemic in his village.

Notes:

This is all about a man moving from animal existence via human existence to

an ethical, moral and spititual life. Many equate ethics with divinity. The

atheists and anti-theists can live with ethics, while theists can live with

divinity. Semantics are different, but all share the same purport. No one is

beyond redemption, given enough time, patience and remedy. Man of ethical

nature living on air, water, donated food and no known shelter is a man

without the ten afflictions. He is a man with a mission, spreading goodwill

among fellow travelers marching to the land of peace, serenity, and equal

treatment of all beings.

The diagram depicts a human being from foot to

crown. A foot level being is prone to malice and murder. A crown level being

is an epitome of Spiritual Illumination.

The characters.

Speaking ‘Animalish’ is

having a close and amiable rapport with all beings, men, and animals.

Faunal-Lingual is the

linguist who speaks to Fauna and is a polyglot.

Parrots: People caught up

in maladjusted criminal-justice system enjoy the stability in confinement.

A squirrel is a man who saves for the future.

Chickens: People at the mercy of others and subject to

exploitation.

Ducks: Friendly people.

Birds and monkeys do not save

for the future and live one day at a time.

Peaceful mendicant

radiates peace, harmony, and amiability.

The cows:

men of peace, of giving nature, and not demanding.

The coyotes, foxes, stray dogs, feral dogs, cheetahs or any other

carnivores: Entitlement seekers.

The cattle owner:

A compassionate man.

The Cobra: the naturally evil

person, who could be controlled.

Cobranese:

The language of evil people.

Ganesa, Siva, and

Krishna: The Criminal Justice System.

Carnivores:

Animals and people who take what they want and when they want without

regard for ethics or law.

Donkey:

an uncomplaining hard worker.

Eagle. An icon of pride, strength,

and courage.

Deer and antelopes:

law-abiding people, taken advantage of by criminals.

Elephant: the one who knows his strength and uses it

judiciously.

Honybees: Good

people working hard and saving for the future. They never get any thanks for

their industriousness. People and animals steal from them and they protest

sometimes. They keep their homes tidy. They are organized well. Division of

labor is their forte.

Taking a bath: Physical

purification as a step towards spiritual enlightenment.

Tigress: the demanding

usurper.

The croc: the

indiscriminate glutton extraordinaire.

Riding on the

back of the croc is having control over indiscriminate and

ravenous hunger.

Goat and

Buffalo are the theriomorphic forms of lust and anger.

People with anger and lust.

Bison:

unpredictable, passionate and strong.

Riding a buffalo is

having control over anger, an uphill battle.

Shepherds: People, with

control over their anger, lust…

Mountain

tribes: Ethical people.

Mountain spirits: Primitive

religion.

Riding an elephant: is

having control over one’s own strength.

Whacking a tiger in water with the tail of

a croc: is controlling the inner urges and showing man his

vulnerability when he is out of his element.

Ref. Thuggees existed in

India. Awareness of the Thuggee problem was widely disseminated.

Travelers were more

careful. The British recruited gang members to inform on their brethren.

Thuggee operations were systematically studied and documented, and a pattern

emerged. With that knowledge, the gangs were suppressed.

Some propose that the

Thuggee problem was invented by the then British Raj to control disparate

parts and people of the country.

Thuggee and Dacoity Dept. was put in place with

Civil servant William

Henry

Sleeman becoming the superintendent in 1835 and

later its Commissioner in 1839. A contrarian view:

Krishna Dutta, while

reviewing Mike Dash's Thug: the true story of India's murderous cult in The

Independent, argues, “In recent years, the revisionist view that Thuggee was

a British invention, a means to tighten their hold in the country, has been

given credence in India, France and the US, but this well- researched book

objectively questions that assertion.”—Wikipedia.

|